The type of analysis this blog subscribes to is much more in line with "auteur theory," where the author is one contextual element of a work but not the only one. In addition to the author informing us about the work, the text itself informs us about the author.

(Below, spoilers that assume you've seen Firefly and Cabin in the Woods, or that you don't worry about spoilers.)

Bad analysis of art, after all, starts with assuming the author is something (lazy, or smart, or ideological, or purely mercenary) and then saying the text only makes sense in as much as it coheres to what they are certain that author wanted. Lucas wanted a light-hearted coming of age story, so in as much as the Prequels aren't that, they must have failed.

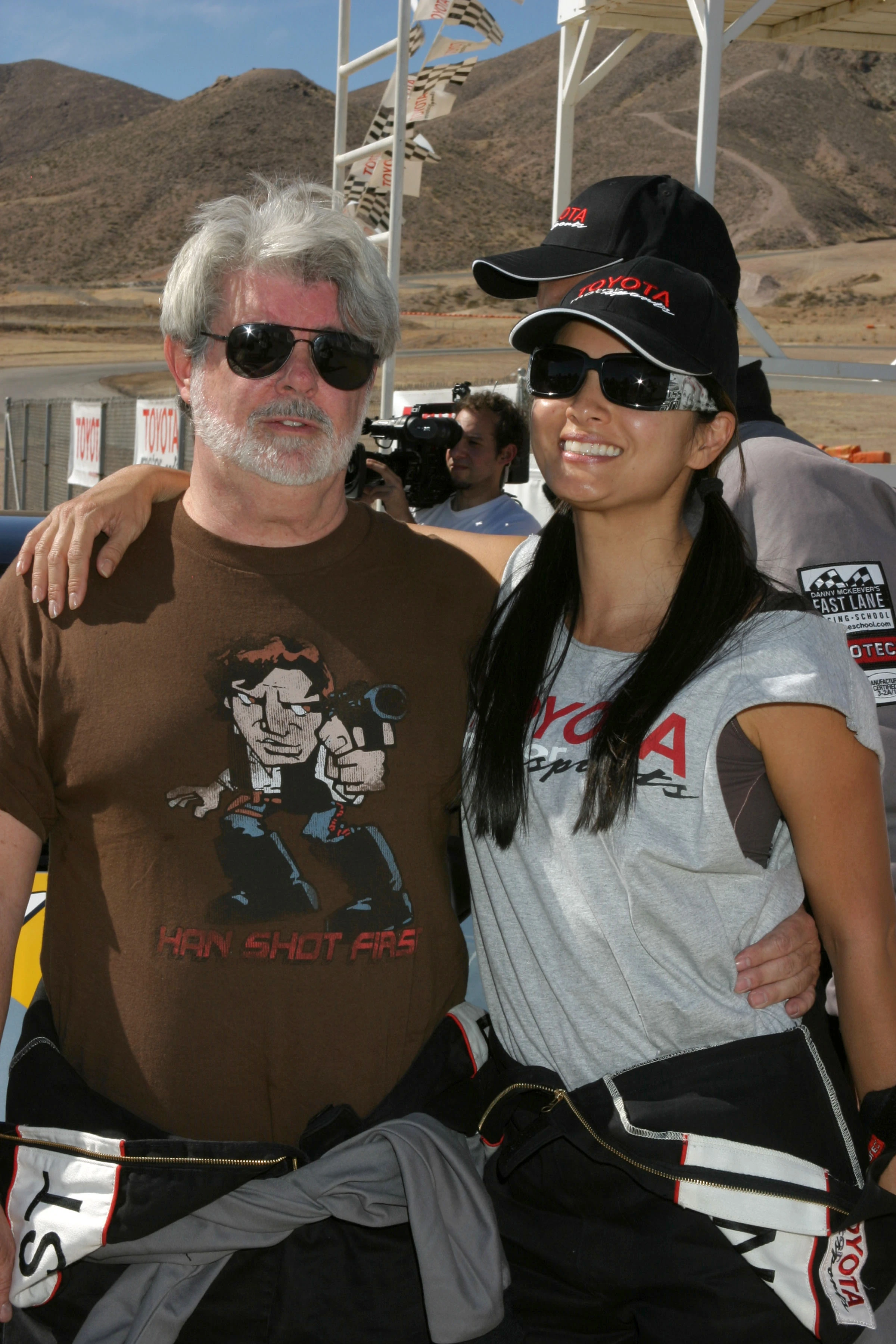

And... no. We don't have direct access to the author's internality. We have some other statements they've made - interviews, random pictures of them wearing shirts, overall knowledge about humanity and his or her culture - but all of these things must be interpreted themselves.

"Han shot first." But what does it mean?

And if you're going to do that, then reading all of the works of the author, the art they put their blood, sweat, and tears into, is the best place to start.

There's no director better for this recently than Joss Whedon. Whedon has been such an immensely successful artist this millennium that one would hope understanding of his work says something about the society that has received it so lovingly.

Quick: What do Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, Avengers, and Cabin in the Woods have in common?

Sure, there's his quippy style of humor, particularly noticeable whenever the characters ratchet up tension, and then deflate it with an ironic metatextual comment. And there's his "television style" of directing, that spends more time on static shots of dialogue than using the camera to tell a part of the story itself - that's in all of these. But beyond that?

You'd be hard pressed to even say his famous feminism (so famous it's now derided as "Whedon feminism") is obviously in all four of these. Not all four have a woman protagonist. Nor do all four have a woman who does kickass kung fu.

So here's something every one of them has in common: there are two distinct sets of bad guys.

There's the chaotic bad guys, who want to eat the entire world starting with you. The basic demons in Buffy, the Reavers in Firefly, the... whatever the name of the very forgettable aliens in Avengers were, and the zombies and monsters in Cabin. They are basically mindless, or when they can voice their desires, it's a complete destructive nihilism. There's no question that these things are evil, and a threat, and that you can't bargain with them.

But, to Whedon, there's always the other set of bad guys too. Buffy has the Watchers who want to control her life. Firefly has the Alliance with its rules and oppression. Avengers had the World Security Council that was going to nuke Manhattan. Cabin had the agency that was running the whole set up, cynically watching innocents suffer while drinking tequila for having completed their quarterly goals.

This second group is Whedon talking about the patriarchy, or kyriarchy, or just the lawful evil complex towering over all of our lives. Given his numerous, numerous public statements in life we can be pretty sure he thinks this group is a big deal.

So you have mindless, all-destroying zombies on one side, and an oppressive state that wants to tell you your role in life, on the other side. (And boy does Whedon like implying that these two groups are related.) And his heroes are stuck in the middle, trying to maintain their integrity to fight the worst of it, without ever giving into the lesser of the two evils.

There is no third option given. Whedon's work never outlines what a non-patriarchal, non-nihilist perspective would look like. There's some tribal affinity for "our small group of cool people should be trusted to do what's right without going too far", but he certainly isn't advocating an overall tribal ethos (like you'll find in Red Dawn.)

We can probably assume Whedon supports a liberal social-democratic capitalism where just the worst excesses of the free market are avoided but otherwise life continues as is in the 21st century West, but only as a "gee everything else is fucked up" resignation. There's no rallying call of "this is a better way."

Which is part of what makes his humor so interesting. Whedon's characters can't bring themselves to believe in anything higher, so their instinctive reaction is to always tear down. Sarcasm is the guiding philosophy here.

This is what makes Cabin in the Woods his most revealing work. Because for once his characters can't escape by the skin of their teeth, and continue their little group's functioning far from both the Reavers and the Alliance, but they actually have to choose. Cynical establishment, or world ending apocalypse. There is no pure choice.

Maybe that's the way it should be. If you've got to kill all my friends to survive... maybe it's time for a change.

We're not talking about change. We're talking about the agonizing death of every human soul on the planet. Including you. You can die with them.. or you can die for them.

Gosh, they're both so enticing.

It's admirable that he doesn't allow them an easy out, but he never even considers a hard out. (Also, notice how the sarcasm plays directly into the nihilism here.)

It's funny too, because you could easily see this last election as a vote between "horrible monster that will destroy the world" and "cynical neoliberal that will change nothing."

***

Bit of a follow up to both the Whedon and Alien discussions.

Joss Whedon is certainly not the only artist to hit on the "enemies in law, enemies in chaos, we're stuck in the middle" theme. Hell, even all give five Alien movies use this. Oh look, the weakest of those, Alien Resurrection, is a Joss Whedon movie.

But it's not a universal theme you see in every work, only one that you see in every Whedon work, and one that plays well with his constant delivery of anti-dramatic sarcasm.

Another significant difference is the attitude of the lawful-enemies. In the Alien franchise for instance, they are inhuman entities whose key trait is they do not give a fuck about you. In the first movie the key phrase is "Crew Expendable" typed out by a remorseless AI. In Prometheus, order is somewhat represented by a grasping Weyland who doesn't care if an alien was just cut out of your body, only if you're standing between him and immortality - but more it's represented by the Engineer race, this angry male god who sees you as little more than an accidental blot on a clean galaxy. Generally all of these forces are willing to ignore you when you don't matter, and expect you to die for them when they desire something.

Whedon's order is a much more human patriarchy. It cares about you, it wants you to submit, and it wants you to be grateful for their beneficence. It wants to change you, into something more useful and obedient (hence why Whedon's Alien movie is the one about biologically manipulating and controlling Ripley.)

Joss Whedon is certainly not the only artist to hit on the "enemies in law, enemies in chaos, we're stuck in the middle" theme. Hell, even all give five Alien movies use this. Oh look, the weakest of those, Alien Resurrection, is a Joss Whedon movie.

But it's not a universal theme you see in every work, only one that you see in every Whedon work, and one that plays well with his constant delivery of anti-dramatic sarcasm.

Another significant difference is the attitude of the lawful-enemies. In the Alien franchise for instance, they are inhuman entities whose key trait is they do not give a fuck about you. In the first movie the key phrase is "Crew Expendable" typed out by a remorseless AI. In Prometheus, order is somewhat represented by a grasping Weyland who doesn't care if an alien was just cut out of your body, only if you're standing between him and immortality - but more it's represented by the Engineer race, this angry male god who sees you as little more than an accidental blot on a clean galaxy. Generally all of these forces are willing to ignore you when you don't matter, and expect you to die for them when they desire something.

Whedon's order is a much more human patriarchy. It cares about you, it wants you to submit, and it wants you to be grateful for their beneficence. It wants to change you, into something more useful and obedient (hence why Whedon's Alien movie is the one about biologically manipulating and controlling Ripley.)

No comments:

Post a Comment