This is a long explanation of capitalist ideology, in response to threads like these.

And direct asks for clarification by @jadagul, @silver-and-ivory, @not-a-lizard, and @kenny-evitt

Okay so what is capitalism.

Well sometimes people are just talking about the economic system. Goods are distributed according to markets, people have control of their private property, and we manage a global financial network by means of far-flung capital deciding what seems like a wise investment. This can be described in the positive sense with no value judgments - although it’s a very complicated system that is usually drastically simplified by anyone without a degree in economics or relevant profession.

But, much more relevantly for discourse, capitalism refers to the thinking that this is for the best. As @jadagul proposes:

Like, if you asked me to define “capitalism”, I would point to the idea that the means of production should be owned privately, and most economic activity should be privately contracted and transacted. And secondarily, I might talk about the ideological underpinnings of divorcing personal, private views from public, economic considerations, which I wrote about here. (Though properly speaking that’s liberalism rather than capitalism, the two synergize).

Emphasis on the word “should.” Which is why we can talk about capitalism in America, and Sweden, and Singapore, all countries with every different economic models and results. In all of them the dominant ideological strain is that a complex system of private exchange is for the best.

Like any belief, there’s a lot of luggage that goes with it.

There are two fundamental arguments for capitalism:

- People’s stuff is their stuff. They should be allowed to do whatever they want with it, which includes selling it to other people who want it for whatever price they can get. We’ll call this deontic reason.

- Markets are the most efficient distribution mechanism for our current stuff, and encouraging more production of it. We’ll call this the consequentialist reason.

These are both compelling reasons, and many tumblrs have made persuasive arguments based on them. But putting them both up there next to each other, we notice something.

…they don’t play nicely together. Like you can’t accept both of these arguments. Either people deserve true control over what they own and it’s okay people starve in order to support this principle – or goods should be distributed based on who will benefit the most from them, and your own claim over them is ethically irrelevant.

(You can try to explain that in our world it just so happens that both of these things are true. That would be very convenient – especially, as noted, this is the dominant belief of those in power. This is extremely unlikely, and in general you should practice skepticism towards claims that sacred values also are practically optimal.)

It’s true that some iconoclasts will bite the bullet, and pick only one of these arguments. Rationalists are pretty good about putting primacy on argument #2, and there are principled libertarians who put #1 above all. But by and large, what do most ideologues say, including “every Republican politician and most of the Democratic ones?” They claim both arguments are true at once.

And when you think of this, especially in the context of “Republican politicians justifying something” you realize that it’s really… just fatuous rhetoric in defense of something. They don’t really care if it’s the most effective system, not enough to test that claim in a falsifiable setting. And they aren’t really committed to deontic property rights. It’s just these are two powerful arguments throw out to win the debate and defend something.

So, to defend what? The naive radical here says that they’re just making these spurious arguments to defend the rich and powerful, but I don’t buy it. No one can buy toadies that passionate, that ubiquitous. They’re defending capitalism the same way you’d expect them to defend American actions in the Vietnam War - ignorantly, but with innocent faith.

So that’s what capitalism is. Capitalist ideology is the thing that people are defending when they make bad, contradictory arguments for capitalism.

The market is not always the worst way of deciding things. But it’s not always the best either. And we need to be able to make reality-based decisions about whether it’s the right principle to follow in any particular policy – but the intellectual forces made to defend capitalism in general, will rear their head to argue that “taxation is theft” and “there’s no such thing as a free lunch” no matter how pragmatic and necessary the left-wing proposal under discussion is. You have to resist that.

You have to ask yourself “okay, but in this area, is mandatory licensing a useful idea? What does the evidence really say?”

***

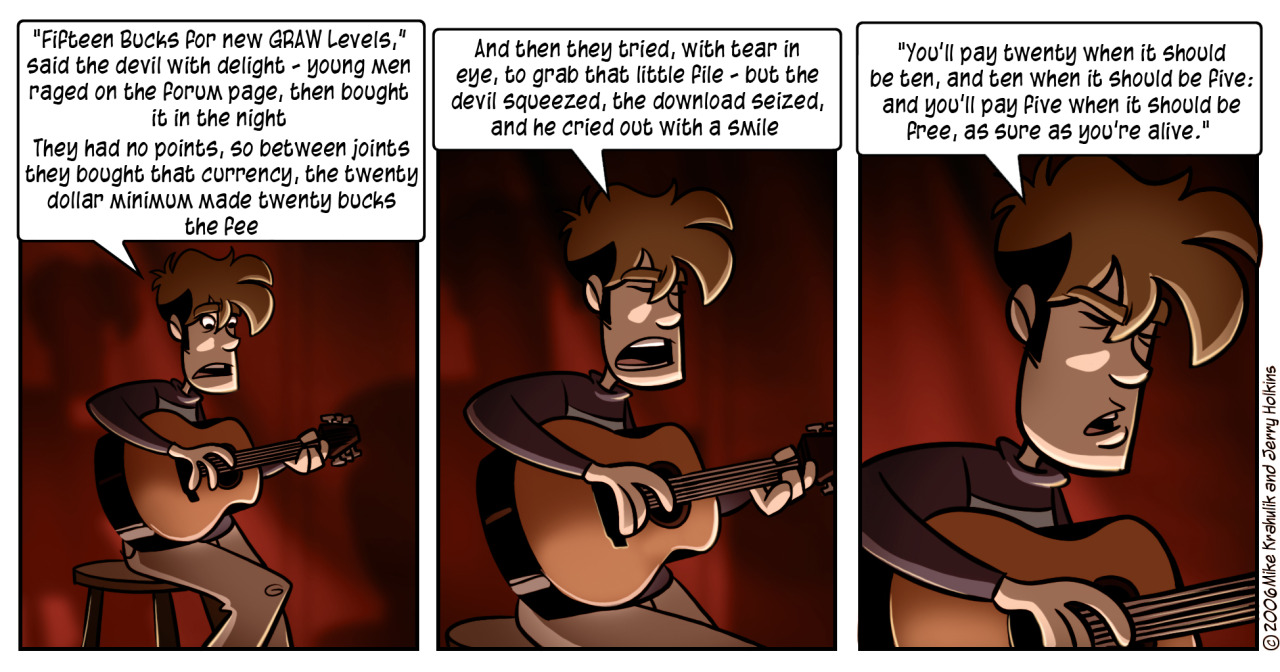

This concern is not limited to the policy realm, which is why we (who have so little influence over policy) end up discussing capitalism so much.

The biggest area where this comes up is the value of people.

Under capitalism, we believe that the value of a person is based on how much money they have. Oh, sure we don’t say this straight out. Every life is equal, etc etc. But whose judgment do we trust?

Who are we more impressed by: our unemployed friend, or the one on a hot track career that affords her a house and fancy vacations, and always buys everyone dinner? What’s the common demand of Republicans: get successful business people into office so they can run government like a business? And when you see someone, how good are you at resisting making assumptions about them based on the niceness of their clothes, their general health and hygiene, and other signifiers associated with class?

Even our judgment of our own productive activities is dominated by this. Here’s an increasing scale we are all familiar with:

- Oh you’re an artist. That’s cool.

- Where you hired by someone to make your art?

- Does it pay?

- Does it offer benefits?

- Is it enough to raise a family on?

… and on and on into even higher scales. The central question of your art (or whatever you do) should be “is it good?” But instead we establish sources of external validation. And capitalism manages to subsume all those definitions of validation, boiling them down to “will someone give you money for them.”

Now, there is often some logic behind these conclusions. The friend who treats everyone to dinner is at least benefiting you. And people paying for your work sometimes means it’s popular which we think sometimes signifies whether it’s good. But these are often short-cuts our mind makes, without thinking about whether that chain of logic really is supported by evidence.

The person who inherited a lot of money, and parlayed that into CEO jobs in their 20’s, and then used that experience as the basis for future claims of expertise, has an opportunity no one else did. And a lot of the companies trying to create media these days are throwing darts in the dark, hoping something hits. There’s a lot of luck, personal connections, and outright immorality that can go into making money, but we still have that shortcut “gets money = valuable.”

So usually what I am getting at when I rail against capitalism, is that I firmly believe unemployed people are valuable too. Not just in some utilitarian calculus, but that their work is interesting, their effort is meaningful, and I enjoy their ideas and think they have a real contribution to society. The fact that at the moment the market won’t pay for it, does not concern me as to the value of their work.

***

Obviously central planning and government can also fuck up. Stalinism and Chavezism can convince people to judge everything based on what the dictator thinks, and that is just as wrong. And statistical evidence shows that a minimum wage boosts income at some levels, and reduces take home pay at higher levels, and efforts to ignore either result are sticking your head in the sand.

But we don’t live under Stalin or another communist dictator. We live in a world where the richest are the most powerful and highest status, and they determine the class ladder. So the ideology we have to be on the watch for is “this that justify the existing capitalist system.”

Regardless, in all such cases - judging policies, or people - we can’t delegate our decisions to ideological short cuts. We must do the hard work ourselves of reading situations and forming our own reactions to them.